Those of you who are long-term residents of Boundary County should think back to an earlier time. Perhaps you are too young to remember, and should ask your parents and your grandparents if they remember when loggers were called tree-killers, land rapists, right-wing extremists, religious fanatics, owl murderers, buffalo hunters or members of a far-right mob.

If old-timers here would like to take a trip down memory lane, they should read Alston Chases’ book, In a Dark Wood: the Fight over the Forests and the Myths of Nature. Chase gives an absorbing account of the environmental movement and the struggle of rural Americans to survive it. I can guarantee you, there are many who don’t want you to remember.

Who’s Afraid of the Big, Bad Logger?

As environmental groups made more and more demands, and refused to compromise with loggers and other natural resource workers, frantic rural people, notably here in Boundary County, people in Troy, Libby, Pocatello and elsewhere across the United States began to network among themselves and organize themselves politically to struggle against the shutting down of the woods and the destruction of their livelihoods. They called themselves “The Wise Use movement.” The movement was national, joined by ranchers, farmers, fishermen, miners, property rights advocates and others.

Environmental non-governmental organizations were horrified at the public favor this new movement received. Surveys showed that the majority of Americans were highly receptive to the idea that we could make use of natural resources without destroying either nature or the economy. The two were not mutually exclusive. The public did not favor pure preservation that would hurt the economy or limit personal freedoms.

The Environmental Grantmakers Association got together to decide what to do about this unforeseen development. Having done research, they admitted that the Wise Use movement was not made up of cronies of the lumber industry, but that they were a truly grassroots movement of moms and pops. The citizens in this movement were mom and pop groups operating out of garages and basements, with shoestring budgets not to be compared with the big bucks donated to their opposition groups.

These people are not wrong, said one environmentalist, they get it. They’re losing their jobs. This is a class issue. They’re right: We are rich. They are saying, these guys live in glass towers in New York. We are the real environmentalists, as we are the ones who have lived and worked and cared for the land for generations.

Nevertheless, the Wilderness report recommended smear tactics in order to win the majority of the public over to their point of view. It recommended painting the Wise Use movement as a far-right, fanatically religious pawn of powerful, special interests. The report suggested writing books, articles and monographs portraying Wise Use as ripping off America and showing the connections between leaders of the movement with other extremists.

Representatives of The Pew Charitable Trust, the Bullitt Foundation and the Alton Jones Foundation worked with public relations group, Fenton Communications, who sent activists to major media centers in Washington D.C. There, they briefed editorial boards, news directors, and feature writers, thereby generating a media blitz in their favor.

The Environmentalists Grantmakers Association decided to smear the Wise Use movement by “exposing” the links between their leaders and “other extremists” such as the Unification Church, the John Birch Society and Lyndon LaRouche.

Yep, that’s it; they’re a far-right mob.

Think about it for a Minute

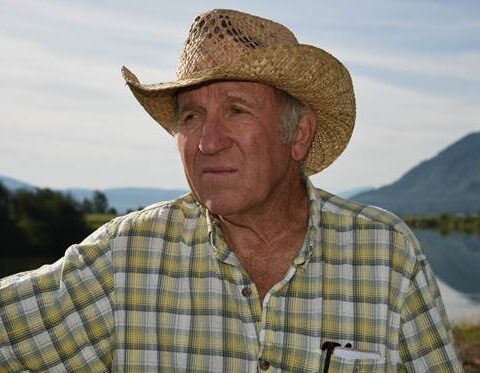

It all sounds so familiar by now, doesn’t it? Question: How many extremist loggers do you remember here? Most of the ones I knew just wanted a few beers after work, and to take their wives or girlfriends out dancing on Saturday night. I did know a logger in Montana who said he was an anarchist, but I don’t seem to remember him doing anything about it. He did eat spaghetti dinner at our cabin once.

Turning Point

Due to this use of smear tactics to convince a mostly misinformed urban population, as well as the support of biased media, the environmentalists were able to capture the sympathy of the American public. Public pressure was put on federal land management agencies, and end runs around Congress and state legislatures were conducted. Circuit court judges were employed to get the decisions special interests wanted.

Because the environmentalists were afraid they were losing favor with the U.S. Congress, they did not seek a legislative fix to the conflict with the Wise Use movement. The Congress was leaning toward Wise Use solutions by then. The Endangered Species Act was due for renewal in 1993, and the environmental groups feared it would be revoked.

So, instead of going to Congress, Bill Clinton and Al Gore decided on establishing an administrative bureaucracy that would deal with the issue. They held the Forest Conference (Forest Summit) in Portland, Oregon in 1993. This conference decided the fate of the Pacific Northwest and California, and, a year later the same treatment was proposed for Idaho, Montana, Utah, Nevada and Eastern Washington. The decisions made then determined the fate of western lands and the people who lived there. I will go into events at that conference more in detail in Part 2 of this two-part series.

Counting the Cost

Chase describes the use of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) to seize control of lands, and its ineffectiveness in recovering species to the point where they could be deemed recovered and then removed from the list. He does say that the enormous amounts of monies budgeted for their recovery was a boon to bureaucratic agencies. Combined costs to all federal agencies for recovery efforts on behalf of the spotted owl and Chinook and sockeye salmon, just in 1992, were $152,415, 671. That amount was for just those three species in that one year. As of 1992, there were 895 species listed and the eventual cost to American taxpayers was estimated at $13.56 billion dollars. Since then, more species have been added. Imagine costs now.

In addition to those direct expenses and monies, he claims that nobody took the trouble to calculate the huge indirect costs of the enforcement of the ESA to America. Indirect costs stemming from increased federal staffers, lands acquisition for sanctuaries, public assistance to the jobless, reduced or terminated business activities, lost jobs, devalued property, foregone tax revenues, and of course legal fees.

Nor had anyone calculated the human and economic impacts stemming from the termination or reduction of thousands of private enterprises affected by the act. As an example of this considerable cost, the creation of a preserve for the gnatcatcher in San Diego County, according to one estimate, would cost local residents $3.46 billion annually and eliminate 28,600 potential jobs.

Destabilization of Rural America

Between 1990 and 1993, 161 mills in Oregon, Idaho, Washington and California closed due to reduced timber harvests. This displaced 14,675 employees, not including loggers or non-millworkers. Since 1980 the region had witnessed the closure of 342 mills with 32,208 mill jobs lost. Many mills here in Boundary County have gone out of business just in the last 25 years and many families have had to leave.

By 1993, NBC Nightly News’ Roger O’Neill reported that, in Northern California alone, five thousand people had already lost their jobs because of the controversy over the spotted owl.

Chase goes on to tell us, “Thanks to logging shutdowns, counties, destitute of funds, were closing schools and hospitals. Poverty spread and families disintegrated. In Grays Harbor County, Washington, the number of food bank users had increased from three thousand to eighteen thousand since 1989, and nearly 90 percent of students in some schools were eligible for the federal food program. A culture of poverty emerged, as aid that attended to the needy—attracted urban poor to the logging communities, where they in turn introduced violence and street gangs.”

In Oregon’s Willamette Valley, there were logging families who had lost their homes and who were camped out in neighbors’ yards and nearby forests. Families argued over finances, and their children began to exhibit emotional problems and destructive behaviors.

Loggers experiencing economic crisis and unemployment in the California Redwoods saw themselves as fast becoming the Appalachia of the West.

This is just touching the tip of the iceberg regarding the devastation of rural America brought on by the environmental movement’s war and the Endangered Species Act.

Aftermath

All the vitriol and devastation poured out on rural Americans did not go unnoticed by Robert G. Lee. When Lee wrote his book, Broken Trust, Broken Land: Freeing Ourselves From The War Over The Environment, he was a professor on the faculty of University of Washington. His area of specialization is the sociology of natural resources, and he is both a trained forester and a sociologist.

Lee grew up in the country and loves the natural world, but he began to counsel displaced ruralites, and to see the pain and confusion on their faces as their jobs, hopes and dreams were destroyed. They had been hardworking Americans who had served their country and lovingly cared for family farms and ranches, yet they were now vilified as nature destroyers, environmental criminals and even worse. They felt their lives had been thrown in the garbage, and they were asking Lee why. He began to study and reflect on the shadow side of the environmental movement.

In Part 2 of this two-part series, I will describe Lee’s journey, his findings and his conclusions.

Note: I previously wrote that the Forest Summit was held in 1992. It was actually held in 1993. I have corrected it above.

Part 2 is found here:

Reinventing Government When Loggers were Right-Wing Extremists

Reinventing Government When Loggers were Right-Wing Extremists Part 2 / 2 – Boundary.News